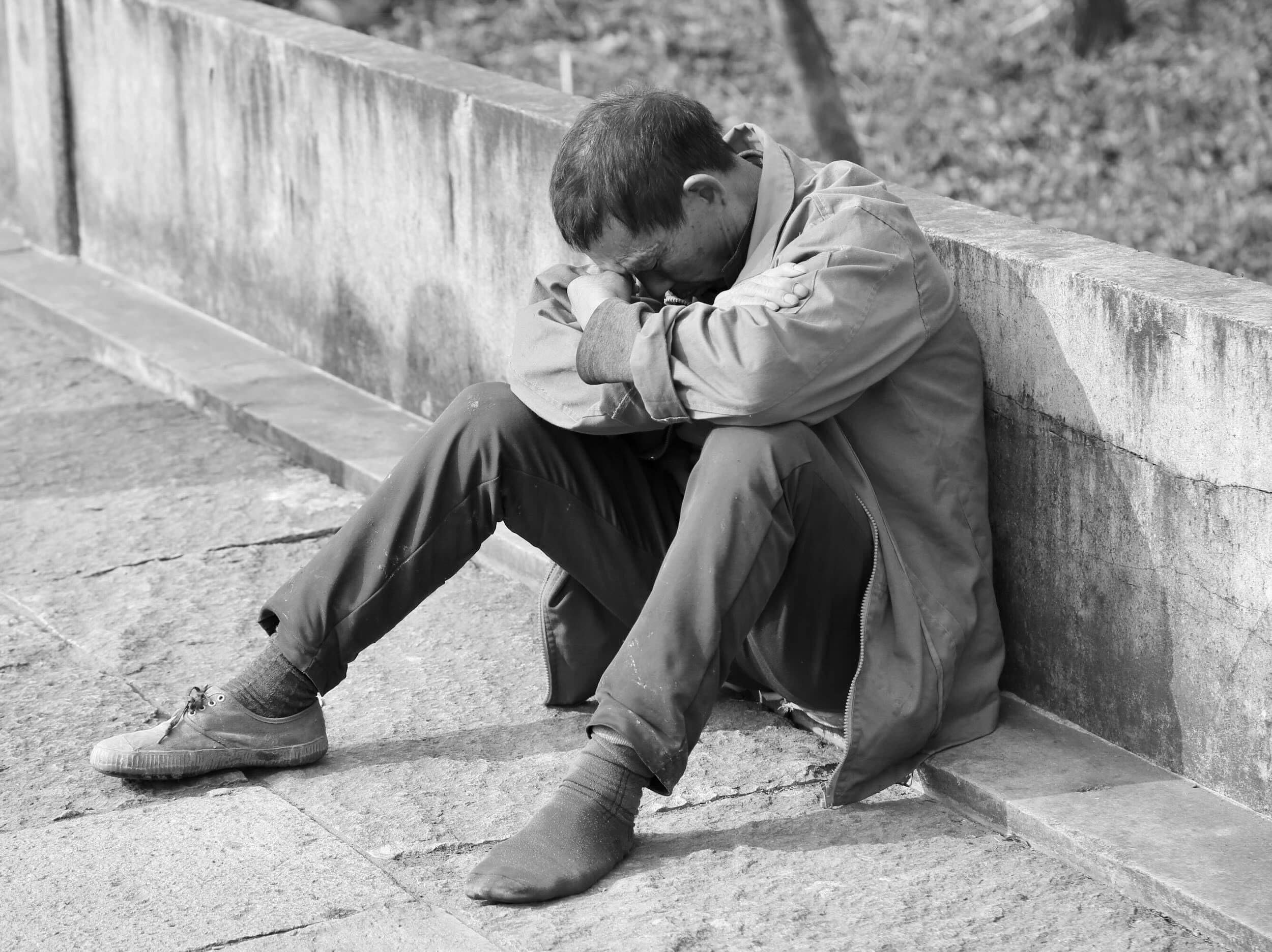

Depression in Men - How is it Different?

What Does it Look Like?

Lakeside Rooms psychologist Luke Foster explains how men experience depression in ways that often differ from what we typically think – and that’s important to understand.

We Often Hear:

“That bloke’s angry.”

“He drinks too much.”

“He’s a grumpy old man.”

“He’s a workaholic.”

Sometimes what we see isn’t the primary problem – it’s the expression of, or solution to, something buried deeper: depression.

Depression in men can hide in plain sight. It’s not always sadness or tears – it can show up in habits, shifts, or patterns that creep in quietly.

Here are six typical ways depression can show in males:

Irritability, anger, or aggression – frequent frustration, outbursts, or conflict rather than appearing tearful or “down.”

Substance use and escapism – drinking, drugs, gaming, porn, or burying themselves in work or hobbies to avoid emotional pain.

Risk-taking and impulsivity – reckless driving, gambling, thrill-seeking, or “don’t care what happens” behaviour.

Physical or somatic symptoms – headaches, gut issues, muscle pain, fatigue, or low libido without a clear medical cause.

Emotional suppression – appearing stoic or “fine” while feeling disconnected, empty, or shut down inside.

Withdrawal and disconnection – pulling away from mates, family, or things once enjoyed. where everyday anxiety can escalate – not because the alarm went off, but because of how we interpret and react to it. When we label the sensation as unsafe, the body listens – the alarm gets louder… and louder… and louder. (That’s panic!)

The differences in symptoms:

Outward patterns are often called externalising symptoms – pain pushed outward. The more “textbook” picture of depression – often seen in women, though not exclusively – involves internalising symptoms (pain pulled inward): sadness, guilt, crying, withdrawal, low self-worth, or changes in sleep and appetite.

Men can and do experience those too – but they’re more prone to show the externalising stuff. Many experience both: sadness, guilt, or low motivation alongside heavy drinking, anger, or risk-taking.

Those outward behaviours aren’t separate from depression – they’re often how it shows up in men. Recognising this doesn’t over-pathologise masculinity; it helps us see the men who are quietly struggling behind the mask.

Why men get missed

Men are diagnosed with depression far less often than women, yet die by suicide around three to four times more. In Australia, about 8% of men report depression (versus 12% of women) – a gap that likely reflects detection bias, not lower distress.

Traditional ideas of depression – and even the tools used to measure it – focus on internalising symptoms. So when distress shows up differently – through anger, withdrawal, or overwork – it often slips through the cracks. It might not look like the textbook version, which means others don’t notice it, clinicians don’t name it, and the person living it doesn’t always recognise it for what it is.

How men learn to hide it

Many men grow up learning to tough it out – to fix, not feel. That self-reliance can quickly turn into silence.

Instead of “I’m struggling,” it becomes “I’m just tired” or “just stressed.” By the time distress shows up, it’s often in disguise – anger, alcohol, or overwork – and gets written off as boys being boys, men being men, personality, or stress, not depression.

From a young age, boys are often taught that emotion equals weakness and asking for help means failure. That belief runs deep, shaping how men cope when life hits hard. Instead of showing sadness, many channel it into action – working longer hours, numbing with alcohol, or flying off the handle.

Masculine norms – the need to stay strong, in control, and hide emotion (which might have their place on a footy field or in a war zone) – are closely tied to these outward patterns and poorer mental health outcomes. When things get tough, many men go quiet instead of reaching out – shutting down, staying busy, or convincing themselves they’ll sort it out alone.

It’s social conditioning at work. Many men have learned to manage emotional pain through doing rather than feeling – to contain it, redirect it, or bury it – until it goes boom!

The result, for some, is undercover depression – distress that doesn’t fit the usual checklist.

The hopeful part

Depression is treatable. Change starts small – doing one thing differently, having one honest chat, breaking one habit that’s been holding you together but pulling you apart. That’s the hard part – and the start of getting your life back.

Depression doesn’t always look sad. Sometimes, it looks like the bloke who keeps saying, “I’m all good, mate.”

Final Thoughts

Depression in men often hides behind anger, overwork, withdrawal, or risk-taking, which can be misread as personality or “just stress” rather than signs of deep distress. Recognising that these outward patterns can be expressions of depression helps shift the focus from judging behaviour to understanding pain, especially in a context where men are less often diagnosed yet face much higher suicide rates. When masculine norms teach men to stay strong, stay silent, and push feelings down, it becomes even more important to name what is really going on and make it acceptable for men to speak up, reach out, and get support.

As always, Lakeside Rooms Psychologists and Psychiatrists are available to help walk this path with you and your family.